Omar Yaghi, the James and Neeltje Tretter Chair in UC Berkeley’s College of Chemistry and an affiliate at the Lab, shared the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his role in the development of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and the techniques for designing and synthesizing new MOF structures – a field termed “reticular chemistry.”

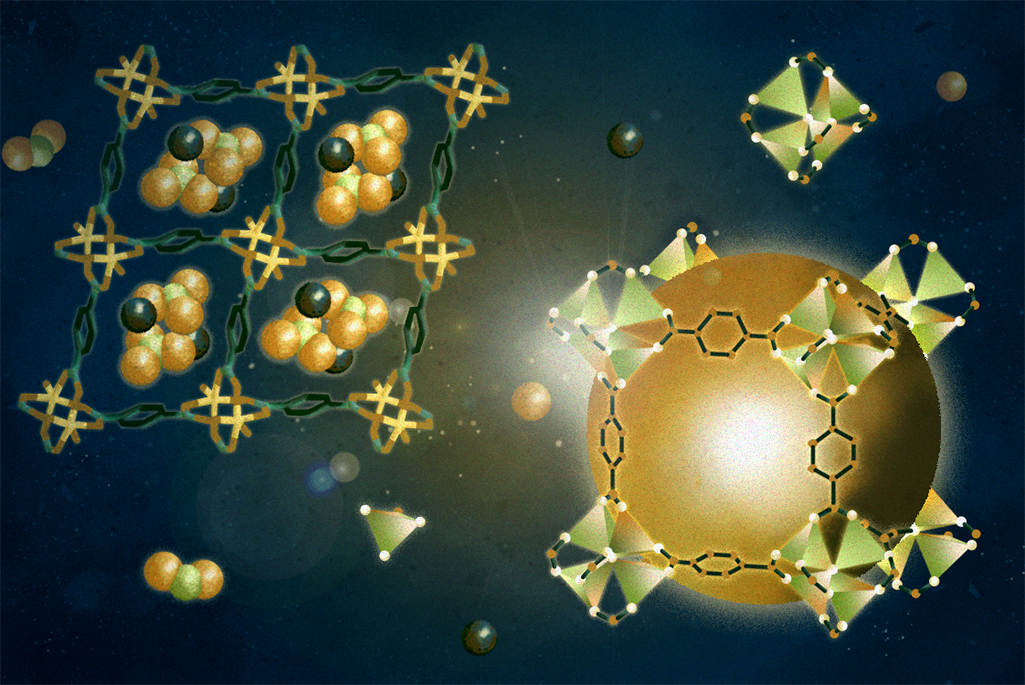

Developed in the 1990s, MOFs are hybrid materials made by binding metal atoms or clusters of atoms to organic molecules in repeating patterns, forming porous crystal structures. The composition and structure of MOFs can be tuned to selectively capture and separate gases and liquids, enabling a wide array of exciting emerging technologies such as next-generation batteries and supercapacitors, platforms for targeted drug delivery, low-cost water-harvesting systems, devices to recover critical minerals from wastewater, and chemical sensors for medical diagnostics and environmental management. MOFs can also be engineered to act as durable catalysts for energy technologies and the synthesis of a wide range of chemicals, and act as conductors with unique properties for sophisticated electric devices.

The structure of MOFs gives them exceptionally large surface areas, so they can hold large amounts of gas or liquid in a tiny volume. For example, one well-known MOF synthesized by Yaghi’s lab has roughly 4,000 square meters of surface area per gram of material. A sugar cube-sized MOF, unfolded and laid flat, would cover a football field.

It is estimated that, to date, more than 100,000 different MOFs – with a huge range of potential applications – have been synthesized and studied, and the field of reticular chemistry continues to grow.

Fueling fundamental research

Yaghi’s foundational work in reticular chemistry was performed at Arizona State University, the University of Michigan, and UCLA, prior to his tenure at Berkeley Lab. Several of the seminal papers cited by the Nobel committee were funded by the DOE Office of Science’s Basic Energy Sciences (BES) program, which supports fundamental scientific research that can lay the foundation for new energy technologies.

Notably, the Yaghi Lab’s landmark 1999 Nature study, which presented the design strategy leading to the first-ever stable MOF and opened the door for all subsequent materials in this class, was supported by BES. Prior to this achievement, the research community had spent several years developing promising, but not yet functional, MOFs.

By the time Yaghi joined UC Berkeley and Berkeley Lab in 2012 as director of the Molecular Foundry, a DOE Office of Science nanoscience user facility, MOFs were a burgeoning area of research.

Since their discovery, Yaghi and other MOF researchers worldwide have relied on Office of Science user facilities like Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry and the Advanced Light Source (ALS) and the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory to synthesize new MOFs and to analyze the materials’ structures and performance. The impact of Yaghi’s work involving the ALS – 60 publications and counting – is one motivation for the upcoming ALS upgrade that will give the facility world-leading, expanded capabilities for a new era of science, including new MOF research.

Moving MOFs to real-world solutions

Building on the foundational Nobel Prize-winning work, researchers at Berkeley Lab and its DOE user facilities continue to push MOF technology to address major global challenges.

For example, at the ALS, a team led by Yaghi traced how MOFs absorb water and engineered new versions to harvest water from the air more efficiently – an important step in designing MOFs that could help ease water shortages in the future. Another team, led by joint Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley scientist Jeffrey Long, used the ALS to study how flexible MOFs hold natural gas, with potential to boost the driving range of an adsorbed-natural-gas car – an alternative to today’s vehicles. An international team of scientists used the ALS to study the performance of a MOF that traps toxic sulfur dioxide gas at record concentrations; sulfur dioxide is typically emitted by industrial facilities, power plants, and trains and ships, and is harmful to human health and the environment. Others have used the facility to design luminous MOFs, or LMOFs, glowing crystals that can capture mercury and lead to clean contaminated drinking water.

Materials scientists at UC Berkeley and the Molecular Foundry have developed a technique that improves the electrical conductivity of certain MOFs by as much as 10,000 times, expanding the possibilities for these materials, which have historically been electrical insulators. The unprecedented combination of a porous structure and conductivity could enable advanced batteries and other energy storage devices, fuel cells, and gas-to-fuel technology. In another advance, Molecular Foundry researchers developed a self-assembling MOF that could extract gas emissions from the air and convert them into useful chemicals and fuels.

“MOFs are of interest for an extraordinarily broad range of potential applications, including gas separations and storage, catalysis, drug delivery, and chemical sensing. We are often able to use X-rays and neutrons provided by DOE-supported national laboratories to directly probe how small molecules engage with the pores within the structure,” said Long, who is a senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and C. Judson King Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering at UC Berkeley. “This provides powerful insights into the mechanisms by which an application may be carried out and how the properties of the material might be improved.”

Long’s group has many MOFs in the development pipeline. In addition to the experimental tools provided by user facilities, they rely on computing resources at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), to simulate how a MOF’s atomic structure will interact with different substances, and to model synthesis processes to ensure they can efficiently produce a stable version of their material. The team recently used the Molecular Foundry and NERSC to design and test a zinc, copper, and chlorine-based MOF that can grab oxygen from air at room temperature, an advance that could significantly reduce the cost and energy required to produce pure oxygen for industrial and medical applications.

“Omar Yaghi’s Nobel Prize illustrates how fundamental research, empowered by the capabilities of the DOE national labs, can translate into real-world impact, and how the discovery of MOFs and other reticular materials can unlock entirely new realms of possibility,” said Jeff Neaton, Associate Laboratory Director for Energy Sciences at Berkeley Lab. “We’re thrilled to see this recognition of Omar’s pioneering work and proud to continue building on the foundation in this important materials class he helped create in our programs and at our facilities.”