When John Clarke and his collaborators Michel Devoret and John Martinis set out in the 1980s to test the boundaries of quantum mechanics, their aim was simple: to determine whether a system large enough to hold in one’s hand could still obey the strange rules of the quantum world.

Supported largely by the DOE Office of Basic Energy Research (now the Office of Science) Basic Energy Sciences program, their experiments revealed that quantum behavior could persist in systems vastly larger than atoms, a breakthrough that laid the foundation for today’s superconducting quantum computers. Four decades later, their discoveries earned them the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physics for demonstrating macroscopic quantum tunneling and energy quantization in an electrical circuit.

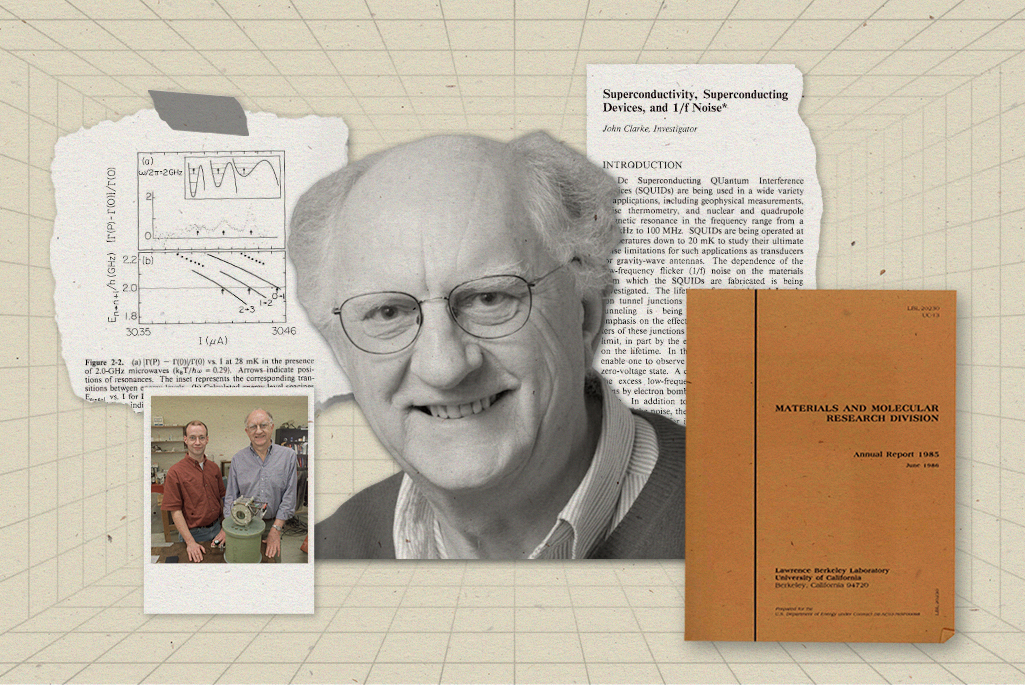

At the time of the prize-winning research, Clarke was a scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and a professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, and he retired from Berkeley Lab in 2010 as a faculty senior scientist in the Materials Sciences Division.

“Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis reshaped how scientists think about matter, measurement, and information. They established the principles that underpin modern quantum technologies, like quantum computation, sensing, and communication,” said Irfan Siddiqi, a faculty scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Applied Mathematics and Computational Research Division, chair of the UC Berkeley Physics Department, and director of the Advanced Quantum Testbed, an advanced superconducting platform for full-stack quantum computing at Berkeley Lab.

“They changed the landscape of quantum science by making large quantum circuits for the first time, which is a significant achievement,” added David I. Santiago, who leads the Quantum Information Science & Technology (QuIST) group in Berkeley Lab’s Applied Mathematics & Computational Research Division.

Decades in the making: A breakthrough rooted in fundamental science

Long before the Nobel-winning studies, Clarke had already built a career exploring the unusual properties of superconductors. In the late 1960s, scientists had invented the superconducting quantum interference device, or SQUID, an ultrasensitive instrument capable of detecting extremely small magnetic fields by exploiting quantum interference in closed loops of superconducting materials. After joining Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley in 1969, Clarke helped refine and extend these instruments, enabling their use far beyond physics labs.

Clarke’s work, alongside that of other pioneering researchers, helped establish SQUIDs as indispensable tools across disciplines including geophysics, materials science, particle physics, and neuroscience, where measuring extremely small magnetic signals provides valuable insights. They were used to map mineral deposits underground, image brain activity, and help search for the dark matter thought to make up most of the universe’s mass and hold galaxies together. Clarke’s group also advanced high-temperature SQUID technology, making these exquisitely sensitive detectors more practical for use outside specialized cryogenic environments.

DOE’s Basic Energy Sciences program supported this work for decades, recognizing both its potential for future applications and its value in deepening understanding of superconductivity and quantum phenomena. That sustained investment laid the groundwork for discoveries that no one could have anticipated.

From a simple circuit to a quantum leap

In the mid-1980s, Clarke’s group turned its focus to the Josephson junction, a core component of SQUIDs that allows electrons to tunnel through a thin insulating barrier between two superconductors. Working at Berkeley Lab with Devoret, then a postdoctoral researcher, and Martinis, a graduate student, Clarke designed a small superconducting circuit that could be precisely cooled and controlled.

When they measured how current flowed through the circuit, they found something remarkable: instead of behaving like a regular electrical device, it acted like a single quantum particle. Despite being composed of trillions of atoms, the circuit occupied discrete, atomic-like energy levels and could tunnel through an energy barrier in a way predicted by quantum mechanics.

Their 1984-85 experiments demonstrated macroscopic quantum tunneling and energy quantization in a visible, engineered object, bridging the gap between abstract theory and tangible devices that could be built and refined.

What began as a test of quantum theory opened new technological frontiers. The Josephson circuits used in Clarke’s experiment became predecessors of today’s superconducting qubits, the foundation for many modern quantum computers. Clarke’s later research explored how these quantum systems could be measured and controlled with minimal noise, helping to define the tools now used in quantum engineering.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say that Clarke’s work paved the way for quantum computing,” said Sinéad Griffin, deputy director of Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and a staff scientist at the Molecular Foundry. “But it has also been profoundly inspirational to later generations of students and researchers and has opened up incredible new possibilities in all these other fields that he couldn’t have predicted.”

Beyond computing, Clarke’s pioneering SQUID research transformed experimental research. Variants of his devices are used today to detect faint magnetic signals from the brain and heart, analyze magnetic properties of geological samples, and search for elusive traces of dark-matter particles or axions. At Berkeley Lab, SQUID-based amplifiers continue to be central tools in fundamental physics experiments that push the limits of sensitivity and precision.

Accelerating the quantum future

Clarke’s Nobel-winning research exemplifies the long-term vision of DOE’s Basic Energy Sciences program. Support for fundamental studies of superconductivity and quantum materials in the 1970s and 1980s made it possible for Clarke and his collaborators to pursue ideas without knowing the extent of the eventual applications. That patience and continuity enabled discoveries that now underpin multiple 21st-century technologies.

As DOE Under Secretary for Science Dario Gil noted following the Nobel announcement, the laureates’ discoveries continue to shape quantum research across DOE’s national laboratories and collaborations. Following the Clarke group’s 1985 breakthrough, DOE-supported investigations have steadily advanced the field for several decades. A recent DOE Basic Energy Sciences Advisory Committee report concluded that these efforts form the basis of today’s most promising routes to quantum computing, many of which involve the same superconducting circuits and quantum effects that Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis first observed 40 years ago.

Clarke’s experiments bridged the gap between observing quantum mechanics and engineering it. His experiments demonstrated that quantum effects can be harnessed at human scales, launching what many now call the “second quantum revolution,” in which quantum effects are deliberately harnessed for sensing, communication, and computation.

The work also exemplifies how discovery unfolds at national laboratories, where world-class facilities, long-term investment, academic collaborations, and the collective ingenuity of talented scientists make it possible to pursue bold ideas and see them through.

“The work of Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis is a beautiful example of how discovery science can unfold,” said Jeff Neaton, Associate Laboratory Director for Energy Sciences. “You start with a fundamental question, and over time, the knowledge and tools developed to address it transform entire fields. The impact of this foundational research will continue to inspire quantum science for years to come.”

DOE continues to push the frontiers of quantum computing through its five National Quantum Information Science (QIS) Research Centers, which includes the Berkeley Lab-led Quantum Systems Accelerator. Berkeley Lab is also partnering with industry and academia and working across the quantum research ecosystem — from theory to application — to fabricate and test quantum-based devices, develop software and algorithms, and build prototype computers and networks.

From the first delicate SQUIDs to today’s quantum processors and dark-matter detectors, Clarke’s research traces a continuous thread through decades of discovery. It shows that when scientists are given time to explore the unknown, they often find answers to questions no one yet knew to ask.