When Carl Haber, a senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Physics Division, first heard the crackling sound and the voice of Alexander Graham Bell emerge from a recording made nearly 140 years ago, Haber exclaimed, “We got him!”

The recording, from an archive collection, dates back to the 1880s at the very beginning of the development of recorded sound technology. Hundreds of the items – mostly discs composed of wax, foil, plaster, or glass, on metal, paper, and cardboard substrates – comprise the collection that resides at the Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, and in Canada’s Alexander Graham Bell National Historic site, in Baddeck, Nova Scotia.

“These recordings shed light on a really important period of innovation and invention in the United States,” Haber said. “They are from a period in history, the last 25 years of the 19th century, when there was a tremendous amount of innovation occurring: the invention of the light bulb, of moving images, wireless technologies and emerging radio communications.”

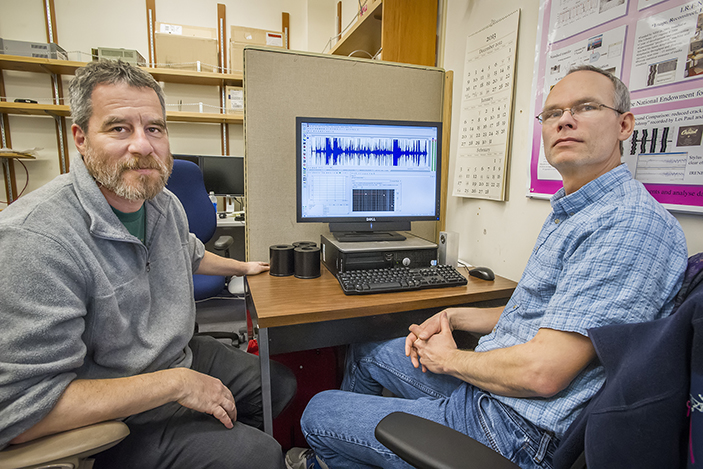

Haber and his research partner Earl Cornell, of the Lab’s Engineering Division, began working together in 2010 on the portion of the archive in possession of the Smithsonian.

“We worked with the Smithsonian and the Library of Congress to restore two dozen of the roughly 400 items from this collection,” Haber recounted. Their success became the basis of a popular 2015 year-long exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

“It was the first time that Alexander Graham Bell’s voice was heard in public” since his death in 1922, Haber said.

What’s it like to hear the sound of a voice not heard for a hundred years? Haber says that sometimes the sounds emerge little by little, “a couple of words or a syllable or two.” But when it’s played in its entirety “your heart kind of jumps,” he says. “Those sensations only come into your life very infrequently.”

That experience laid the seeds for an ambitious restoration and rejoining of the items in the collection held in both the United States and in Canada.

Haber and Cornell came close to realizing that dream in 2019 with funding promises from private donors and both the U.S. Interior Dept.’s National Park Service and the Canadian government. But the plans came to a halt with the onset of the COVID pandemic. Commitments withered away and priorities shifted as the world went on lockdown.

“The National Park Service didn’t take the money away but they said we could return to [the project] when conditions improve and we found additional donors,” Haber said.

Throughout the pandemic period they searched for financial support for the project, finally landing matching private funds from recording industry impresarios Linda and Mike Curb, Seal Storage Technology, and monies from SEDDI Inc. and the Alexander and Mabel Bell Legacy Foundation.

Much has changed in the intervening years since the 2015 Smithsonian exhibit.

Haber and colleague Vitaliy Fadeyev originally developed technology from instrumentation and methods used for detecting and measuring particles created at high energy colliders, such as the facility at CERN near Geneva. He used that non-invasive tech to measure the physical grooves etched into the materials used for the sound recordings. Cornell, the principal software engineer, provides the means to interpret the measurements and play back the sounds recovered. Today’s technology is both faster and much more precise, Haber said.

He added that much of the improvement came while working on a project with UC Berkeley’s Dept. of Linguistics and the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology to restore some of the museum’s 3,000 ethnographic recordings of indigenous peoples.

“That three-year project taught us a lot about how to operate and run a large-scale project like the one we are embarking on now,” Haber said. “Scanning day in and day out, processing a lot of data, archiving that data, and documenting it.”

Once the Bell recordings restoration project is complete, Haber says he’d like to go back to restoring ethnographic field recordings, specifically a trove of 6,000 recordings at Harvard University made by Oakland-born scholar Milman Parry, who traveled the former Yugoslavia during the 1930s studying and recording the oral traditional poetry of Serbia and Croatia.

“It’s fascinating,” he said. “These were people singing long folktales from an oral tradition passed down for generations; whose structure goes back thousands of years to the epic poetry of Homer.”

Related articles and links:

Alexander Graham Bell’s voice 1885

Berkeley Lab Scientist Named MacArthur “Genius” Fellow for Audio Preservation Research

What Did Alexander Graham Bell’s Voice Sound Like? Berkeley Lab Scientists Help Find Out